Articles from the wikipedia processing thread:

- 1 - Understanding the Wikipedia Dump done

-

2 - Processing the Wikipedia Dump

2 - Processing the Wikipedia Dump done

Okay, we’ve already understood the Wikipedia dump format and that’s great! But judging how much information we have inside of it, how can we process and index it in a more manageable way than a single XML file? This is exactly what we’re going to do here: processing the bz2 archive. Yeah, the archive itself - more on it soon. So, for me, there are usually 3 steps into this whole “processing” phase:

- reading the data efficiently

- formatting the data as needed

- saving the data efficiently

The “efficiently” thing on steps 1 and 3 is just because we have to be pragmatic in such phases, we really need to think through it. When reading we need to be cautious with our time, and when saving we need to be cautious with our space. The step 2, formatting, is a bit of an odd space for me… sometimes there are requisites that we need to match and so we don’t have too much control over it - but when reading and saving, we do.

All the code in here will be provided as Scala3 code, but it’s fairly easy to translate it all to Java, it’s almost a 1 to 1 translation - since I almost don’t use functional operations in the code, and pattern matching can easily be replaced by if-else blocks in Java 11 or less and it’s literally there on Java 17 and up.

Lets go over those steps to begin with.

Reading

So, I’ve said we’re not supposed to “unzip” the bz2 archive before processing it, and there are multiple reasons for it, but the main one is space and time - oh, the “efficiently” thing. You might remember the Wikipedia dump link in the first post, and you’ll probably see that are two types of bz2 archives for pages: the first one is the “enwiki-20220220-pages-articles-multistream.xml.bz2” and the second one is the “enwiki-20220220-pages-articles.xml.bz2”. So, what is this “multistream” about? You can find a pretty shallow explanation here on this Wikipedia page (who the hell is going to use dd to manipulate a 20GB file that should be processed? Come on man…), but I’ll try to explain it a bit better.

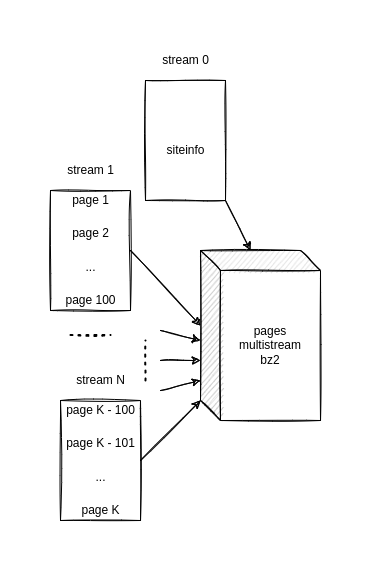

A “multistream” bz2 file can be thought of as: the concatenation of multiple files with the intent to make it easier to search for anything that is included into this archive when their stream position is known. Explaining it a bit better: every file, per say, becomes a stream, and those streams can be separated by counting the size of such files in bytes - after compressed. Therefore, on the Wikipedia dump page, right under the enwiki-20220220-pages-articles-multistream.xml.bz2 file, which is the dump archive itself, we have a enwiki-20220220-pages-articles-multistream-index.txt.bz2 index file containing the number of bytes of each stream inside that file. For example, imagine that we have 3 files made into a bz2 archive, and we know the first stream have 100 bytes, the second stream have 300 bytes and the last stream have 180 bytes. If we want to read something from this archive, without extracting it, and we know is inside the 3rd file, we might go straight into the third stream jumping 100+300 = 400 bytes into the file and we can get only this stream that will for sure obtain the needed data. I KNOW, I KNOW, YEAH YEAH, I KNOW there are some bytes that come into the compression before the data itself forming a header, but we’re trying to make sense of those things here, okay? We’re just trying to make sense of things, but if you want to go that deep into it, GO. In the case of Wikipedia, each stream contains 100 pages, no matter how many bytes, and the first stream of the file is dedicated to the siteinfo part of the dump aline - remembering our siteinfo object.

The image below should shed some light on how those Wikipedia dumps are built, and why the bz2 archive and the index file work they way they do - this is just how I see it:

Hopefully the archive structure is clear now. Lets begin to code it.

Reading it

If you’re inside this Java World, I believe you know Apache Software Foundation and their amazing projects. And one of those amazing project, is the Apache Commons Compress, which we’re going to use so we can easily access and process data inside of this bz2 archive - yeah, inside of it, no decompress beforehand is needed, which is amazing.

The class Bzip2CompressorInputStream is where all the magic happens, it takes a InputStream as the constructor. So, all we have to do is something like the method below:

object StreamLoader:

val log = LoggerFactory.getLogger(this.getClass)

def getStreamBuffer(inputStream: InputStream): ArrayBuffer[Byte] =

var ba = ArrayBuffer[Byte]()

synchronized {

try ba ++= BZip2CompressorInputStream(inputStream).readAllBytes

catch

case e =>

log.debug(e.getMessage)

return null

}

ba

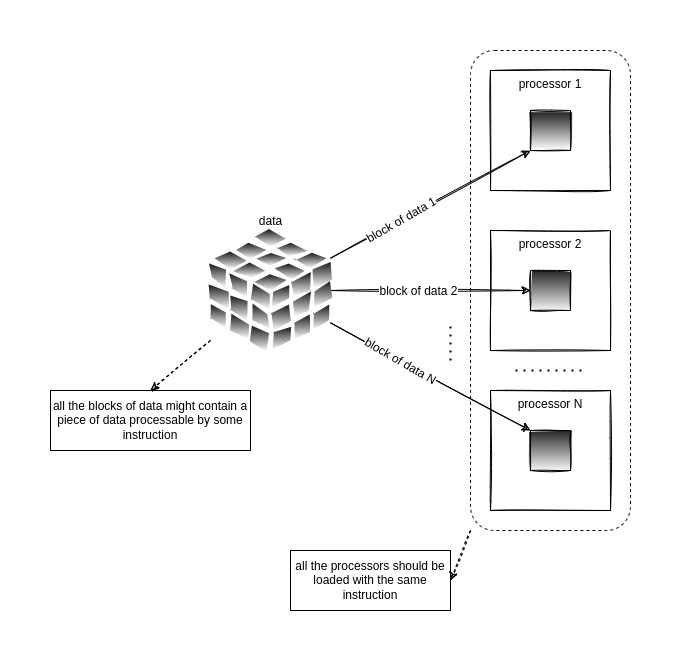

The synchronized block there might be an indication what we’re going to do, right? Yes, we’re going to call this single method from multiple threads! That’s why we create it inside an object and not a class, so it’s static and the concurrent model takes place - one thread has access to read, while all others wait to get a piece of data to process. If you’re big into computer science theory like myself, you’ve probably seen it before on a computer architecture or distributed programming class before… yes, this goes into the Flynn’s Taxonomy on Single Instruction stream, Multiple Data streams [SIMD].

Making it easier: we have a single operation to apply over data that might be divided beforehand. The diagram below is how I usually see this kind of operation:

We can abstract those processors as threads and the block of data as a stream, and voilá. People will surely say that I’m stretching the concept of processors and instructions here, and YES I AM. But, this hasn’t failed me yet - specially when using a VM language and not coding on bare metal. But pasmen: even on bare metal with C, MPI and OpenMP, with a 4 machines cluster, it hasn’t failed me yet!

Something I haven’t told you, but you should have seen by now in the XML dump, is that it’s actually formatted like this:

<mediawiki>

<siteinfo>...</siteinfo>

<page>...</page>

<page>...</page>

...

<page>...</page>

</mediawiki>

So, as I’ve said: first block stream will give you the siteinfo, BUT it comes with this <mediawiki> tag like this:

<mediawiki>

<siteinfo> ... </siteinfo>

And so the following streams are going to give you 100 pages at a time, BUT it’s going to end wiki a </mediawiki> tag like this:

<page>...<page>

<page>...<page>

...

<page>...<page>

</mediawiki>

And this thing right there will give you problems when processing this with any kind of XML Stream Reader (we’re going to talk about it in just a minute, hold on). Also, any XML Stream Reader will demand that all those tags are “embraced” in the form of a single document, so they can’t be like this, they should be part of a single other document tag. Therefore, what you’ll need to do is having a method to put this stream of pages INSIDE another document, such as:

def getDocumentStream(inputStream: InputStream): InputStream =

val content = getStreamBuffer(inputStream)

if content == null then return null

val ba = ArrayBuffer[Byte]()

ba ++= "<document>".getBytes

ba ++= content

ba ++= "</document>".getBytes

BufferedInputStream(ByteArrayInputStream(ba.toArray))

NOW, you have a processable entity by any XML Stream Reader that you get from a provider. Because your streams (on a good day, not the last one as we’ve seen) will come as:

<document>

<page>...</page>

<page>...</page>

...

<page>...</page>

</document>

So now we have a starting tag <document> and an ending tag </document>, as we should have in a well-formatted XML document.

That’s a lot, I know, but those are all the ins and outs I can think off when reading those streams in a proper way to be processed. The processing is rather interesting too, lets jump right into it.

Writing it

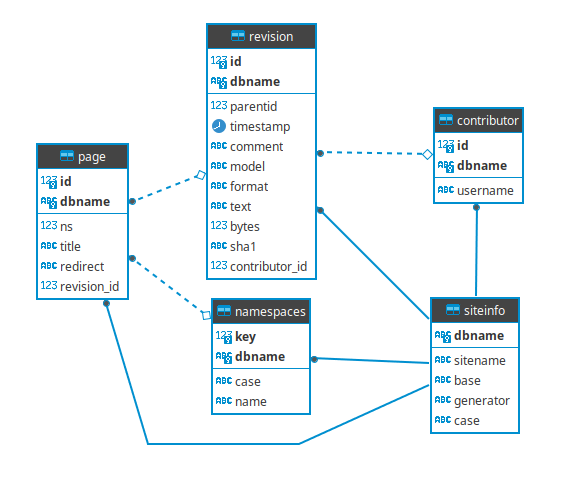

Well, as I’ve said before: I’m writing it to a postgresql database but you can write it literally to anything you want as long as you have the drivers or the means to do so. Lets remember how the data is structured inside the database:

In the code I’ve used this idea of a SinkSender, that’s just something to “flush away the data” from the program into whatever place it should be. To do so, in Scala, I created a trait which can be relative to an interface in Java, as displayed below:

trait SinkSender extends Closeable:

def sendSiteinfo(siteinfo: HashMap[String, String]): Unit

def sendNamespace(namespace: HashMap[String, String]): Unit

def sendPage(page: HashMap[String, String]): Unit

def sendRevision(revision: HashMap[String, String]): Unit

def sendContributor(contributor: HashMap[String, String]): Unit

def dispatch: Unit

def close: Unit

And as we can see, I have a send type of method for each entity of the code that will go straight into the database, but they don’t go from there into the database until the dispatch method is called. Since we’re processing it 100 pages at a time with each stream, I’ve found it very practical to just use batch operations for those 100 pages at a time, so the send methods only call the addBatch inside of a connection until the dispatch method is called and then the executeBatch is called for everyone - in a very specific order, as you might remember from the usage of foreign key constraints. This controlled point of synchronization also allow for a document to be build and sent into an Apache Kafka topic for example - but I’ll not go deeper here since it might be confusing enough already.

But for now, all you have to understand is this SinkSender structure, and build your own from there. Check the repository and see how I’ve done it all and also a bit more to build the whole database structure I need from the code itself.

Processing it

Now, I’ll show you an easy way to process it without going too much into the details. Here, I’ll probably not show you all the code, but will show you how to do the code. If you want to see all the code, you can see it directly on the repository.

When processing the data, I chose to use the java built in XML Stream Reader. I don’t have time to go deeper into the XML Stream Reader thing here, but here is a good enough tutorial about it.

Obviously, when processing a 20GB+ Bzip2 archive, you’ll not try to load it all into the memory, right? RIGHT? Okay. So having streammed operations like we’ve already done when reading the file, and then processing the data step by step so we can extract information needed without searching for it - because the whole document has a well formatted schema - seems like the best choice. This is exactly what this XML Stream Reader gives us: a way to process the stream step by step, going from tag to tag, until we reach the end of each block and get ready for the next one.

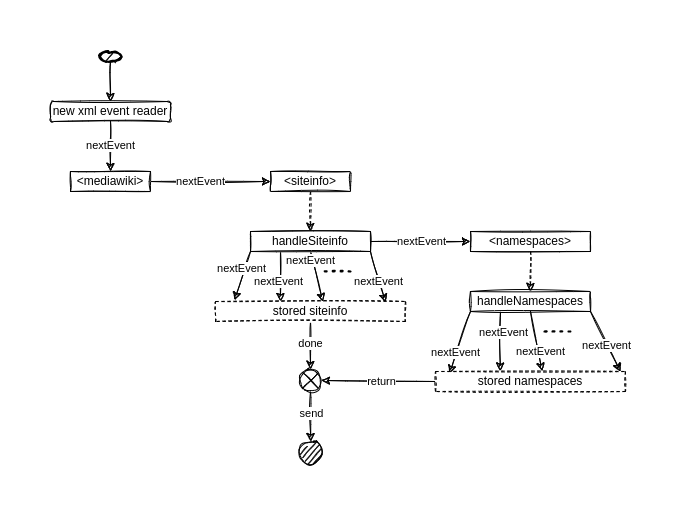

I’ve chosen to do so using handle methods for each kind of object I have on this XML dump. I don’t think it’s very practical to display whole chunks of code here, since it might become extensive and tiring to read, so I’ll display diagrams and explain them while trying to make sense of the code I’ve already written and that should guide you in the path of writing your own or just using mine.

Below is a diagram of how the XML Stream Reader and the handle thing should work for the siteinfo object, exactly as it is:

I know it might seem confusing, but this is just a way to imagine the function expressed as a flow chart, and most of the times it helps me wrap my head around some details. Let’s follow the flow chart step by step, with some code snippets:

-

create a new XML event reader, those are available globally inside this class

class XMLStreamHeaderProcessor( sinkSender: SinkSender, xmlif: XMLInputFactory, inputStream: InputStream ): val log = LoggerFactory.getLogger(this.getClass) val xmler = xmlif.createXMLEventReader(inputStream) ... -

call the “nextEvent” method until you reach a desired tag, in this case, the

siteinfoXML tagdef run: String = var dbname: String = null while xmler.hasNext do val xmlne = xmler.nextEvent if xmlne.isStartElement then val xmlse = xmlne.asStartElement xmlse.getName.getLocalPart match case "siteinfo" => ... -

call a handle function for this tag to extract the desired information, returning information to the caller function so you can mix needed data like connecting foreign keys

val siteinfo = handleSiteinfo -

once you’re done collecting information and mixing them with any needed information from the handle methods and their returned info, send it

def handleSiteinfo: HashMap[String, String] = val siteinfo = HashMap[String, String]() var namespaces = ListBuffer[HashMap[String, String]]() while xmler.hasNext do val xmlne = xmler.nextEvent if xmlne.isStartElement then ... else if xmlne.isEndElement then val xmlee = xmlne.asEndElement xmlee.getName.getLocalPart match case "siteinfo" => sinkSender.sendSiteinfo(siteinfo) namespaces .tapEach(ns => ns.put("dbname", siteinfo.get("dbname").orNull)) .foreach(sinkSender.sendNamespace(_)) return siteinfo case _ => ...

There are a lot of optimizations in the code, for example: no dispatch was called when sending the siteinfo or the namespace, and that’s because it’s not needed and much more practical for the operations to be done instantly since all the pages being inserted later need both of those operations to be in the database so the foreign keys are connected properly. So, in those cases, the send calls are actually SEND calls, no operation batch needed.

Another example of those optimizations are those early returns that should instantly cut the function and return to the caller. Might not be much, but since we’re dealing with ~20M pages, every instruction counts - and it would honestly be hard not to do it.

All the careful treatment of null values is needed to extract valid information and also the invalid ones. When dealing with such data, usually coming from websites or raw user input (maybe not here since this data should be carefully managed by the Wikimedia friends), I’ve learned that we should never trust data and even with some errors we should let the code go ahead so we have something to analyze later - and beyond all of it, sometimes null is a valid entry.

Once again, if you’re reading this just to get a glimpse of the idea and to write your own processor, go ahead! But, in case you just want to use something that someone has already started, take a look at my github repository containing this code.